The flip side of pop art

Waldemar Januszczak and Audrey Ward

After Warhol, pop art underwent a controversial revival in Russia and China. On the eve of a Saatchi show, Waldemar Januszczak looks at how the work cocked a snook at dictators, while Audrey Ward interviews the artists.

[…]

Alexander Kosolapov

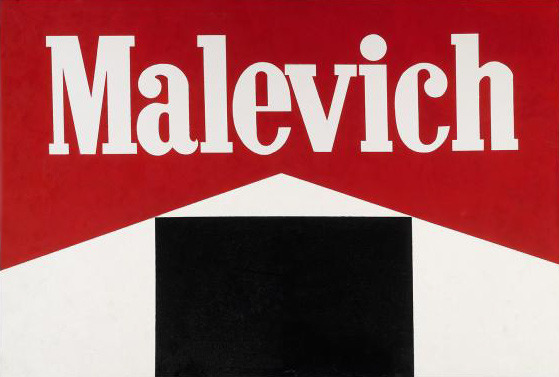

Malevich: Black Square (1987), by Alexander Kosolapov, rekindles the familiar Marlboro logo (© Alexander Kosolapov; courtesy of the Tsukanov family foundation)

Kosolapov’s Marlboro, Malevich series tackles the subjects of art history and our consumer culture. This image re-creates the instantly recognisable cigarette packet, substituting the word Marlboro for Malevich — a reference to the Russian artist Kazimir Malevich.

When he emigrated from Moscow to New York in the 1970s, Kosolapov saw plenty of similarities between the two cities, despite living through the Cold War era. He started to compare “the social icons of the two countries” and found himself marrying images of communist ideology with products of western mass culture — cue his profile of Lenin with the Coca-Cola logo.

Eleven of his works appear in the Saatchi exhibition, including his 2007 bronze sculpture Hero, Leader, God, depicting Lenin and Christ hand in hand with Mickey Mouse.

Kosolapov fully embraced the notion of pop art as revolutionary from a young age: “I approached it as a kind of mockery, and started to criticise those small groups who were in power and were ignoring human issues.” The Muscovite’s cheeky use of religious symbols, including a doleful-eyed Christ alongside the McDonald’s logo, outraged the Russian church.

Although inspired by Russian culture, Kosolapov despairs of his homeland’s autocratic society, and of Vladimir Putin, whom he calls “cynical”.

“I had illusions in 2000 that Russia could be a more open society and I started to work with Russian curators, but that turned out to be a delusion and the situation is the same today,” he says. Despite creating so much art, he’s no collector, preferring to line his walls with books instead.

Source: www.thesundaytimes.co.uk

Comments are closed.