Art and Morality under Neoliberalism: Reflections on “Blasphemous” Art from the East—A Tale in Three Parts

Ania Szremski

[…]

Part II: Russia and the Icon

If the new Poland has since entered a period of relative normalcy, both culturally and economically, the same cannot be said of the new Russia. From the early 1990s to the 2000s, Russia has witnessed the aggressive deregulation of the private sector in tandem with Vladimir Putin’s re-nationalization of profitable companies. Such a volatile combination has led to rapid economic growth alongside severe authoritarian corruption.

In the midst of these changes, a series of artistic experiments cheekily (and sometimes violently) tested the boundaries of the public sphere. In this predominately male, Moscow-based context, we again witness historical avant-garde tactics of shock and awe, aimed at shaking up bourgeois mores. However, the emphasis here, unlike in Poland, tended to be less on the sexual and more on the scatological. Artists were ultimately concerned with the destruction of the beloved icons of Russian society, both art historical and religious.

Avdei Ter-Oganian was a leading figure during this time. Founder of the “Art and Death” group in 1989, Ter-Oganian co-founded Moscow’s first artist-run space/squat on Trekhprudnyi Lane in 1991. During the gallery’s short lifespan, September 1991 to May 1993, Ter-Oganian and his fellow artists staged about ninety one-night exhibitions in their small space.

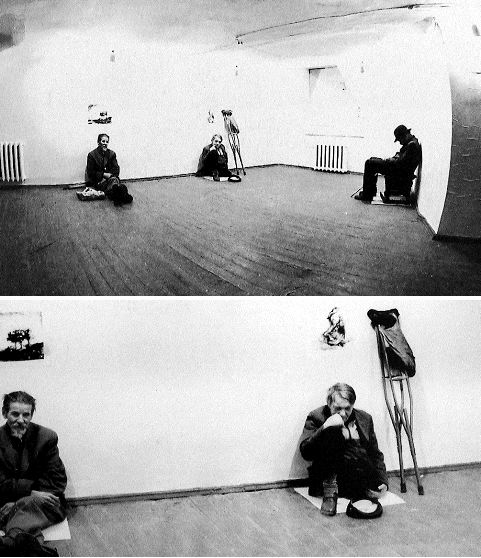

Konstantin Reunov and Avdei Ter-Oganian, Charity, 1991. Drawings and performance.

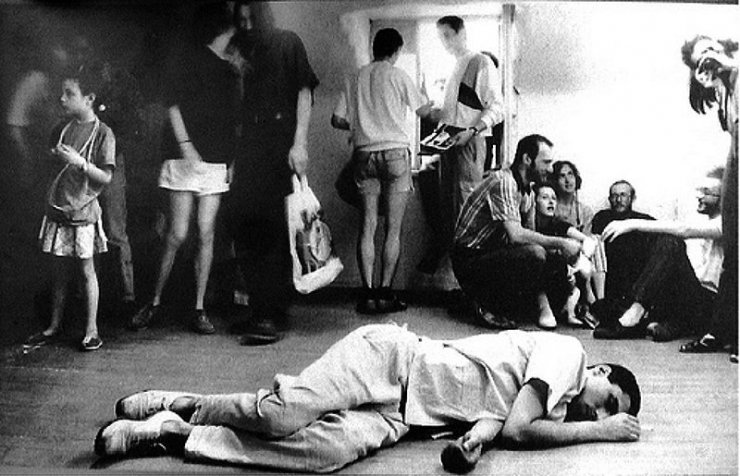

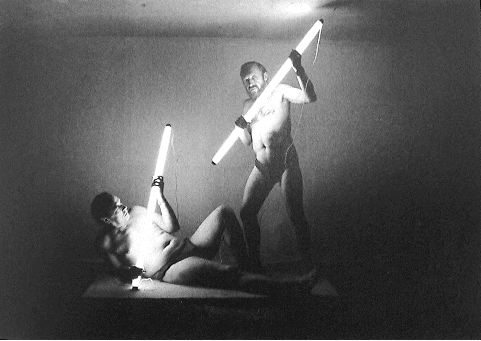

Highlights include the gallery’s first event, Charity, organized by Ter-Oganian and Konstantin Reunov, for which the artists hired three street beggars to sit next to three reproductions of etchings by Rembrandt (including the eponymous work, Charity). In the Moscow performance of 1992, Ter-Oganian, Alexander Kharchenko, Alexander Gormatiuk, and Vladimir Dubosarsky organized a four-hour-long bus tour of Moscow that included visiting the city’s best liquor stores.[10] In Neonacademy, two models were hired from the Academy of Fine Arts to pose nude with neon lamps. And in Towards the Object, Ter-Oganian drank himself unconscious and remained passed out in the middle of the gallery for the duration of the one-night exhibition.

Avdei Ter-Oganian, Towards the Object, 1992.

Performances in which bodily excretions played a central role were popular. Modest Pupils of the Great Master, for instance, was an homage to Piero Manzoni’s Merda d’artista: Ter-Oganian invited artists to contribute their feces to an exhibition installed inside a refrigerator, which was later donated to the Moscow Museum of Contemporary Art. In her paper “Controversial Performances at the Moscow Gallery on Trekhprudnyi Lane,” art historian Joanna Matuszak discussed another example, in which Ter-Oganian recreated Duchamp’s Fountain, but restored the readymade to its original function:[11] A urinal was mounted to the gallery wall, and copious amounts of beer were served to the opening’s attendees; the bathroom, however, was locked and declared to be out of order, forcing those in dire need of relief to make use of the artwork itself. Interestingly, Matuszak notes that the performance is clearly for a male viewer; female attendees would be hard-pressed to participate. In general, the work by Ter-Oganian and his cohorts often revolved around the male body, the phallus, and stereotypes regarding the Slavic male’s inherent machismo.

Alexander Gormatiuk, Konstantin Reunov, and Avdei Ter-Oganian, Neonacademy, 1992.

Despite the bold and sometimes salacious content of the works shown at the Trekhprudnyi Lane gallery, these experiments were safe enough from the wrath of censors. The squat’s relative isolation from the general public—and the artists’ preoccupation with dismantling art historical hierarchies (as opposed to local/social ones)—made the performances less interesting to state officials. But Ter-Oganian began to get in trouble when he turned his attention to the icons of Russian religion.

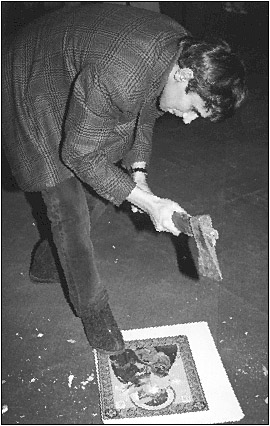

At the Manege Art Hall in 1998, the artist performed Young Atheist, in which he wielded an axe and attacked mass-produced icons belonging to the Russian Orthodox Church. Unlike his earlier experiments, this performance would not slip under the radar. Following a public outcry, the curator of the exhibition was fired from the gallery, and a lawsuit was brought against the artist for “activities aiming to rouse religious hostility, accomplished in public.” Ter-Oganian subsequently fled to the Czech Republic, where he has since remained, in exile to this day.

In this instance, it was not the vulnerability of the exposed body that caused offense, but the destruction of objects that embodied traditional values. Critics feared losing the icon, an object that reaffirmed notions of home and tradition, as well as one that preserved a sense of continuity in a moment of extreme change. Furthermore, the very public and participatory nature of the performance made the piece downright dangerous (Ter-Oganian invited viewers to destroy the icons themselves or, if they chose, they could pay him to do the dirty work).

Avdei Ter-Oganian, Young Atheist, 1998.

The Young Atheist performance launched a series of the most incendiary cases of censorship in post-1989 Russia. In January 2003, the exhibition, Caution: Religion!, at the Andrei Sakharov Museum and Center in Moscow was vandalized by followers of the ultra-rightwing Orthodox priest, Alexander Shargunov. Criminal charges were brought against the museum director, Yuri Samodurov, the curator Ludmila Vasilovskaya, and the artist Anna Mikhalchuk for “incitement of ethnic, racial, or religious hatred”—a violation of Article 282 regarding blasphemy in the Russian criminal code. Although charges were ultimately dropped against Mikhalchuk, Samodurov and Vasilovskaya were convicted in 2005 and each fined 100,000 rubles. Tragically, in 2008, Mikhalchuk was found dead, presumably from suicide.

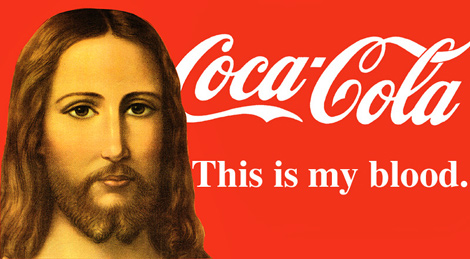

Alexander Kosolapov, This is my blood, 2002. Light boxes, 82 x 150 cm.

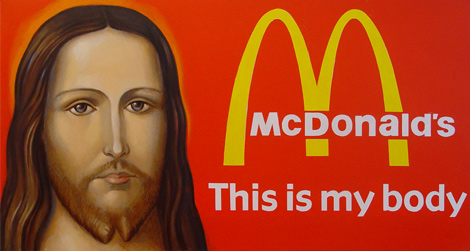

Alexander Kosolapov, This is my body, 2002. Light boxes, 82 x 150 cm.

At the Sakharov Museum in 2007, Yuri Samodurov found himself in hot water again. That year, Samodurov and Andrei Yerofeyev co-curated Forbidden Art, an exhibition of all the artworks censored by Russian museums and galleries in 2006. Several of the pieces were again religious in theme, such as Alexander Kosolapov‘s Icon-Caviar and This is my blood, This is my body, the Blue Noses Group‘sChechen Marilyn, and Vagrich Bakhchanyon’s The Crucifix. In 2010, the curators were each fined 5,000 dollars for inciting national and religious hatred—a light sentence in comparison to the three years’ imprisonment with which they had been threatened.

Blue Noses, Chechen Marilyn, 2005. Color photograph, 75 x 100 cm. Edition of ten.

Other cases of censorship have, of course, been overtly political—for instance, when the Russian government refused to allow Ter-Oganian’s Radical Abstraction series to be shown at the Louvre in 2010, due to the artist’s attacks on Putin and other governmental officials. The most troublesome work, according to Russia’s Ministry of Culture, was an abstract painting of a black bar floating in a red field that bore the label, “This work urges you to commit an attack on statesman V. Putin in order to end his state and political activities.”

But that case aside, the most dramatic and detrimental cases of censorship were carried out under the banner of morality. In an open letter to the Louvre curator, Marie-Laure Bernadac, Ter-Oganian claimed that this was due to the increasing political power of the Russian Orthodox Church. Of course, the extraordinary personality of Putin himself is another unique factor in post-Soviet Russia’s culture wars. But beyond these local specificities, deploying words like blasphemy and morally offensive to attack the arts is an attempt to drain a “thick” discursive sphere of true critical potential. From this angle, then, there is little difference between the condemnation of Ter-Oganian under Putin and the condemnation of Mapplethorpe under Reagan. […]

Source: www.art21.org